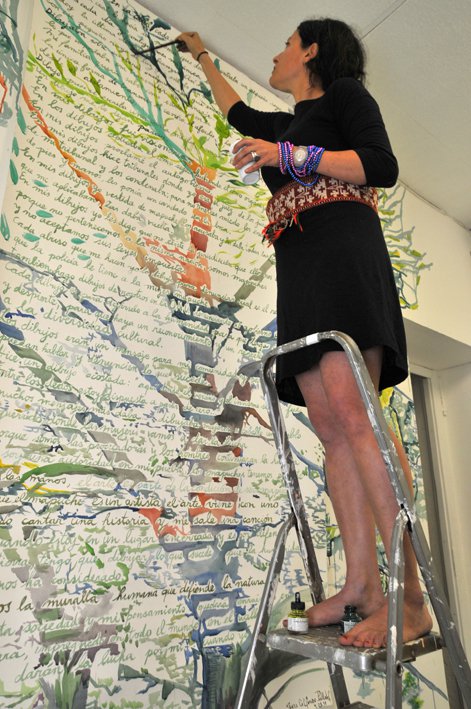

Artist Spotlight: Marisa Cornejo

Marisa was born in 1971 in Chile. Her family fled Chile after the coup d’état of 1973 and the subsequent dictatorship. The neo-colonial nature of orchestrated coups and dirty wars that followed in Latin America along and the context of the Cold War provided the background of her upbringing. Since leaving Chile she has lived in multiple countries, including Argentina, Bulgaria, Mexico, the United Kingdom, France, and Switzerland. Her experiences as a Latin American refugee are still in dialogue with her artistic expression today. Besides being a visual artist, Marisa is also a performance artist with a background in contemporary dance. In our conversation we focus on her use of dreams as the methodology guiding her art, the gradual development of her practices of expression and her current and upcoming projects.

Creative journey to self

Her father, an art teacher, encouraged Marisa and her brother to be creative and inventive. She describes being surrounded by different materials to work with on the table and being dissuaded to use colouring books in favour of trying things on their own. “If something didn’t work, there was another way to approach it. There was no wrong way of expressing ourselves.”

She recalls one of her first drawings made in Argentina after her father handed her and the other children paper to draw while he and other adults were close by, talking about “terrible things that had happened to them or might be happening to their friends in Chile in the secret prisons.” She explains that although back then she did not understand drawing as a form of expression, she realised later that this was one of her first instances of expressing deeper emotions and feelings through visual language rather than words.

“I drew some naked people, and I was feeling a bit disturbed or ashamed that I had drawn naked people on this piece of paper. But I guess I was already trying to tell things that I was hearing or seeing from the situation we were in, as unrecognised refugees. I didn't know I needed to express these difficult things. But then when I did the drawings, I was like, oh no, I don't want these to be seen by anybody. To me it was a bit shameful, but while I was in the process of drawing, I was probably already channeling things I needed to say, and I had no words.”

Even though art was a significant part of her upbringing, she decided against studying art at university. “I didn’t want to repeat the history of my father, my grandfather and my great grandfather who were all art teachers, you know?” She adds with a smile. She pursued a career in contemporary dance instead. Yet eventually, after coming to terms with the challenges of having a contemporary dance degree in Mexico, she made the decision to study visual arts at the National Autonomous University of Mexico – one of the biggest in Latin America with a significant role in the region.

Contemporary arts became a different language for Marisa through which she was able to critically revisit and re-examine her experience and relation to art practice. “I started to see all the wrong things my father taught me”. Specifically, the role of the body: its movement, its presence, its contents. “The movement of my body as a presence that talks by itself, that contains the archive of memories of the lost territories and ways of being and allows the archive to have a voice.” Eventually this culminated in Marisa starting to work with her dreams as a manual instruction to do performances. She traces that process to her experience with dance: “this comes very much from the body, it demands the body to take the voice, take action in the world and reach out to others in solidarity."

Gaining this understanding first required challenge and failure. “You ask, how did I have the courage—it’s because I failed as a contemporary artist, I tried to play the game of placing large objects in the white cube, but I failed. I became dependent on money, substances and people and I hurt myself a lot in the process.” For contemporary artists in Mexico, in her experience some of the project funding came from US institutions such as the Rockefeller Centre. This was confronting to Marisa as it meant coming face to face with, and becoming financially dependent on, the representations of imperialist institutions that partook in the damage of her country. “It created too many contradictions.”

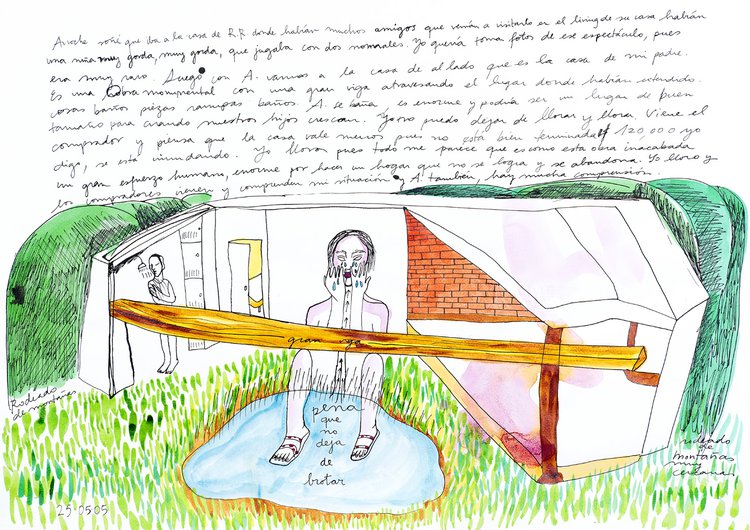

“When I was completely defeated, I had to retreat myself from this arena. Go back to my father’s house, try to find another solution. I started to draw my dreams, do something honest from within that wasn’t anymore to occupy a place or convince people about something. It really became a dialogue with the trauma that inhibited my body, and then I started to draw my dreams systematically.”

Creative Process and Recurring Themes:

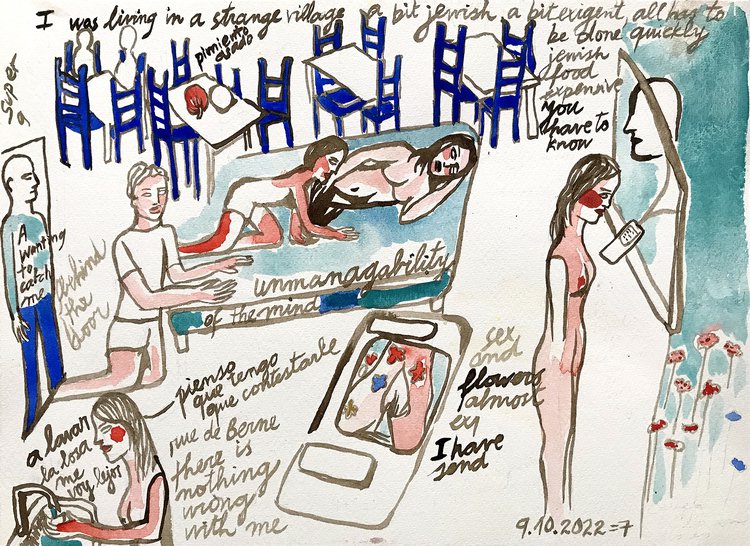

Marisa tries to always be surrounded by drawing materials – something that she is used to ever since her childhood. She shows me around, and I see inks, paper, other drawings. As her dreams are her inspiration she will paint and draw when she wakes up or throughout the day. “It’s almost like a gymnastic, I dream of this, I don't think about it, I just draw it.”

She has used her dreams as a methodology for 26 years now, so she is able to reflect on how her practice has changed over time. She specifically reflects on the use of colours. In earlier practices of drawing her dreams, Marisa took a more rigid approach: “In the past, in my first years when I was drawing dreams, I thought ‘this has to be read’. I was like a designer. […] I knew exactly which colour and how to compose it on paper. I was a perfectionist.” Now, after years of practice and taking inspiration from other artists using colour in dynamic ways, the use of colour has gained a role beyond aesthetics. “One day I will not be here anymore, and I hope that people can feel a little bit of these worlds and they can believe in them. And not think ‘oh she was just doing nice stuff’, I was not just doing nice stuff. I was believing in these other worlds and transforming myself by doing it."

She explains, “Lines and perfect shapes and perfect colours can be really cool, especially on the screen. But material pigments and accumulation of colours and lines can have an animistic presence. The colours attract you, the colours vibrate, they talk to the soul not the mind. Colours are symbolism to reterritorialise memory”. Dreams and the process of drawing them is not merely an art style but a method closely intertwined with spiritual guidance: "we dream mothers earth dream, the silenced voices of our vulnerability in a world where torture has been normalised." In that way, drawing her dreams is not merely an expression but also a way of processing, understanding and transforming.

Just last night, she explains while showing me her most recent dream drawing, she dreamt of technology. “There is a phone, another phone— I have been dreaming about technology and social media recently. And the relation of my body to that.”

“This technology is a way of either colonizing or being colonized. These devices are extracting all of our little clicks to be transformed into capital. Capital, as Enrique Dussel developed through many years of studying Marx, is the Antichrist. So how can my spirit deal better with technology? that is what my dream is trying to understand."

As her dreams inspire and guide her expression with the subconscious embodied memories, there are diverse themes that emerge, she mentions: displacement, reparation, reterritorialization, and possibilities of reconfiguration of identity and gender.

She is, as she describes, on a quest of citizenship and belonging. The Chilean state has never provided reparations to her, similarly neither has any other state. “I am still a refugee that never received reparations.” As a woman from the Global South the intersection of gender, migration and the body are evident by what she describes as the 'cost of integration'. Having ‘tested out’ living in England, tested out France and now trying out Switzerland, the challenges of being a migrant are compounded with the challenges of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Yet through working with her dreams Marisa is able to work in locating her own identity and coming to terms with her perceptions of reality. “But this [internal] work means that I still haven’t found my own place. But I am not in despair anymore, […] this is not something that happens to Marisa, but something that happens to any women in this position, this quest of deterritorialisation beyond this way of life” Her art practice therefore, is also an approach for personal spiritual development.

“These dreams where I am trying to find my territory, when I'm trying to find my father (who died prematurely due to torture and exile as an unrecognised refugee—when I try to recover the territory that was stolen to us. It comes very often and often there are lawyers or there is money or they're not helping me, or the people are wanting to trick— you know? In war and displacement, you are always in a dangerous place— and so you’re asking, is this a dangerous place as well? Who can you trust? In my dreams I am still asking myself to search for peace. As a quest – not as a destination.”

When it comes to the themes of territory or home, Marisa is inspired by the historic and cultural ties between the Al-Andalus and the territories colonized by the Spanish, like Chile. She reflects on the territory of the Al-Andalus in which Muslims, Jews and Christians developed knowledge in collaboration before being expelled. The element of expulsion and loss of territory share commonalities with Marisa’s life experience. These elements further appear in her dreams like the small from her father’s house: “What I need to rescue from the dream, is the smell of the house. It’s not even the territory, it’s just the smell of that house comes from the Andalusian cooking” She further describes sometimes listening to the music of the Andalusion ‘siglo de orco’ music while working. It is evident throughout our conversation that the use of all the senses is significant in her art practice.

Art Scene and Current Projects

She experience the art scene in Westernised art spaces as “bourgeoise and conservative” or, “a profession where people have to be privileged to continue to work forever in the art [space].” Emphasising the challenges in breaking into the art scene. She goes back to Chile or other territories often “to touch ground because that is where the problems of our communities are. But in that sense Geneva has being a good place to have a global vision, all passes through Geneva, even the price of the petrol and the biggest transactions cross the networks of Geneva every night, so it has being a good place to get a critical vision."

As the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup d’état in Chile is coming up she is publishing the book 'L’empreinte', a memoir of her father’s life with the Swiss publishing house Art&fiction which will come out in January 2023. She is also working on an exhibition, 'No Monuments in Le Commun' with the Chilean diaspora in Geneva. She has previously created videos in which she explores places of her own exile mixed with the art archive of her father and recovers feelings and visual materials that expand one her feelings of belonging through performances. She adds that in preparation for the anniversary she will continue editing other work, in which she interviews survivors, thinkers and social workers to be weaved with footage of her performances.

All the while, she is working on two projects with INSPIRE researcher Katarzyna Grabska. One of them, lectures alternatives she describes as an ‘ambitious project’. The project brings together mixed identities of migrants in different museum spaces in Switzerland where they discuss Swiss identity through art collections with the aim of challenging and de-stigmatising migration.

This has further prompted her to consider the space of the museum as a space of dialogue and will create a workshop in the Musée d-ethongraphic de Neuchatel. “I thought, a workshop aimed at mixed migrant identities together with the friends of the museum. I hope they both come, and we can draw together there and see if some of the pieces remind them of things they have seen in their dreams."

“I don’t know what is going to happen” she admits, “but to me that’s already interesting” .

You can find more of her work and stay updated on future performances and exhibitions on her website: